In this interview, we spoke to Julie Gagoe Tchoko and Merline Touko Tchoko, two sisters from Bafang in the Uper Nkam department of the West Region, Cameroon, who have been working with Synchronicity Earth as affiliates in our Congo Basin Programme since 2021. With their local and cultural knowledge, these members of our team provide a vital bridge between Synchronicity Earth’s London-based programme staff and our conservation partners.

Julie has over 15 years of experience working for international organisations monitoring and evaluating development projects, particularly with a gender equality and community-led focus. She provides support to Synchronicity Earth’s field partners, assisting them with monitoring and evaluation, helping them to integrate gender into the tools they use on a daily basis to monitor and evaluate their activities in the field. She is responsible for the initial review and analysis of progress reports sent in by these field partners. This approach to monitoring combines both virtual and face-to-face exchanges and training, as well as field visits, helping partners to improve performance and effectively demonstrate the impacts of their interventions.

Merline is a communications expert, journalist and author. She has worked for several international research and sustainable management institutions over the last 13 years, helping them to develop and implement their communications strategies. Merline has a degree in organisational communications and, like Julie, she has studied a Master’s degree in Natural Resources Management. Merline supports Synchronicity Earth’s partners in the Congo Basin by helping them to present their results effectively, strengthening their communication tools and implementing communications activities adapted to the realities of the region.

In this first part of our discussion, we explore the personal experiences that shaped their desire to protect the Congo Basin and its communities, and learn about some of the challenges of working in this unique environment.

Q: Can you tell me about your relationship with nature and why and how you came to make a career out of conserving the natural world?

Julie: I’ve been interested in nature since we were both very young. Our parents instilled in us the importance of our relationship with the land. We grew up in the West Region of Cameroon, an area that is quite environmentally degraded, but where our late father had combined fruit trees with shade trees and created a little green oasis that was quite different to the rest of the town, where most trees had already been lost.

“One thing I understood very early on: if you want to eat, you need to work the land, and if you treat it well, the land will nourish you.”

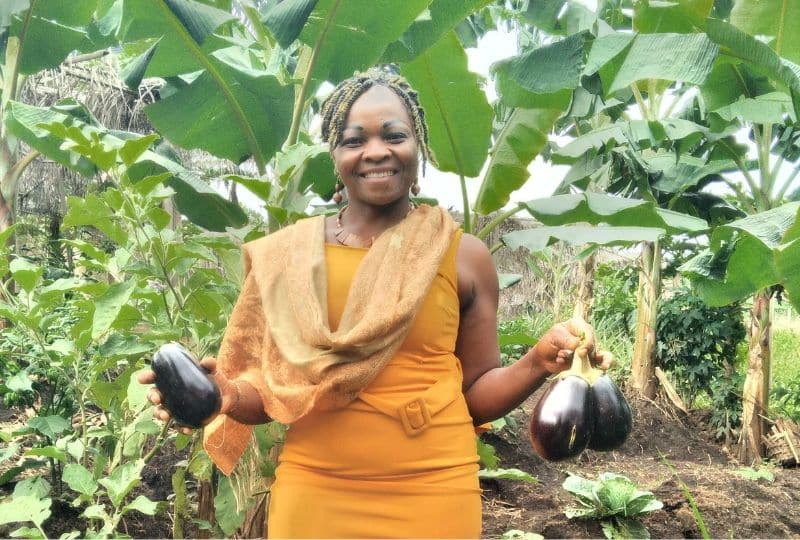

In her role as Congo Basin Affiliate, Julie provides support to field partners, particularly regarding gender.

Merline: When we were little, we had a tree behind our house. It didn’t produce any fruit, so our father decided to cut it down. I was upset because I’d become quite attached to it.

My father told me OK, if you look after this tree and give it what it needs, then I won’t cut it down.

He gave me time to take care of the tree. And less than six months later, it had started producing lots of fruit! To this day, that tree still produces fruit…

“What I learned is that sometimes you need to give something a second chance, whether that’s a person, an animal, a tree; what doesn’t seem important today, could be very important tomorrow.”

And it wasn’t just trees, fruit, and vegetables – my father also helped us to learn about animals. We raised a whole menagerie of animals, like cats, guinea pigs, even snails.

Our childhood environment was one where we were in harmony with nature, with other species. It was an easy decision to work in the conservation field, to protect nature.

Julie and Merline’s parents instilled in them the importance of looking after the other species we share our planet with.

Julie: My early attachment to the environment around me nudged me towards the academic choices I made. I chose a path that would deepen my knowledge of people as part of their environment.

Q: For people who might not know much about the Congo Basin, what makes it so unique as a region?

Merline: When you see an aerial view of the Congo basin, you just see this vast expanse of green.

“This is the second-largest forest ecosystem in the world. Its gift to the world is pure water, and oxygen, it is home to a multitude of plant and animal species found nowhere else on Earth.”

Julie: Yes, and it’s worth remembering that the Congo Basin includes six countries sharing the same ecosystem, the same biodiversity, with all the natural corridors that link these countries together. Animals can move freely between them, which is positive but also creates challenges. It means it is very difficult to quantify the biodiversity that exists in one individual country.

“An elephant might be in Cameroon today, then tomorrow it will be over the border in Guinea.”

The Congo Basin is also home to a huge diversity of human communities, languages, and ethnicities.

“When you see an aerial view of the Congo basin, you just see this vast expanse of green,” says Merline. Image: Chris Scarffe

Q: As a woman, what are some of the challenges you have encountered working in conservation?

Merline: As a woman working in conservation in the Congo Basin, the problem we face is essentially cultural. In our culture, a woman’s role is generally considered to be in the home; to take care of children, and also to bring in some income. But women often have no say in decision making.

Women are often not even supposed to be present when men are taking decisions. Organising any kind of activity as a woman can be extremely challenging in this very conservative social context.

This is the big challenge, simply to be respected as a woman of action.

Although Julie and Merline both pursued careers in natural resources management, they both use different skillsets to serve community-led work in the Congo Basin.

Julie: Yes, I agree. For a woman who wants to be a leader in conservation, it’s a huge effort.

Women have to work extra hard, do more research. A woman in this field has no margin for error, as any mistake can be amplified and used to criticise and demoralise. We are not operating on a level playing field.

But thankfully this does seem to be starting to change.

“If conservation continues without women’s voices, it can never have the same benefits or reach.”

An additional problem is that, in many cases, women themselves lack self-belief; they’ve been taught for so long that it’s the man who makes the decisions that they find it hard to value their own decision-making capacity.

I’ve worked with several organisations helping women to build confidence, to learn to speak and express their ideas in public.

Putting forward women’s interests is a struggle we face every day. That’s why the role of organisations like the Coalition of Female Leaders for the Environment and Sustainable Development (CFLEDD) can make such a difference in encouraging women in conservation. It’s vital that we continue mobilising the funds to support these women.

Another solution is to organise meetings involving the husbands, the men in the community, to ensure they understand the messages we are bringing as women.

Women’s perspectives can contribute not only to the protection and improvement of the environment, but can also help to create a better life at home and in the community. So, helping to develop leaders among local women is great, but bringing their partners into that conversation is even better.

Q: Can you talk a bit about the relationship between biological and cultural diversity in the places where you work, in the Congo Basin and with the partners we both work with?

Merline: I would say that here in the Congo Basin, the question itself is a little illogical. Our culture is interwoven with the forests and biodiversity around us. For example, in the west of Cameroon, the links between our forest environment and our culture are very strong. When we appoint a new head of the community, that person must go into the forest and pass certain tests. These strong cultural ties are really what allows us – what obliges us – to preserve nature, and it’s not just a question for village heads. In many of our country’s cultures we have what we call our sacred huts, often in very specific places, which are used to perform certain rites to maintain the link between our ancestors from generation to generation.

Julie: When we talk about nature, some people think about trees, animals, plants, and so on. But, in general, most local and Indigenous communities in Africa, and in the Congo Basin particularly, don’t see nature in that way. Nature is a place of spirits and spirituality. A tree, an animal has spiritual significance for us; they are the totems of a community. It’s all this value one sees when we speak of the forest, when we speak of biodiversity. We look at the forest not as a resource, but as the link which binds us all together.

Julie has over 15 years of experience working for international organisations monitoring and evaluating development projects.

With modernisation, these links become fragile, they get fragmented. If someone has been away from their village a long period of time, they say that they are going “to reconnect themselves to nature…. going back to replenish their resources.” It’s a place where you feel full of renewal: your ancestors are everywhere, in the trees, in the plants, in the animals, and that gives you positive energy.

When we cut down a tree, just because we need to sell it, along with all the benefits that are lost such as carbon storage, oxygen and so on, it’s a part of our culture that is lost with that tree. We have lost so much already – almost 70% of the forests in our region. We are trying so hard to protect the small amount left, because we understand the value of what we are losing – our customs and traditions – and the kind of sacred power the forest holds.

And we realise that if that continues, we will become a population without a history, without languages, which emerged from the relationship with our environment, a population that is dying. This is not just about Indigenous Peoples – we are all from the forest.