On the week of Synchronicity Earth’s tenth anniversary, Founder Jessica Sweidan reflects on the cultural shifts toward conservation we have seen in the past decade.

Our work on the ground with people, in places where biodiversity is rich and often, the most threatened, is the primary focus of the day to day work we do to deliver our programmes.

But perhaps surprisingly, the biggest challenge we face as an organisation – is not working in the Congo Basin, or in areas like the high and deep seas – it is encouraging people that care, to act.

In the last ten years, we have seen an enormous increase in knowledge and understanding about the environmental crisis – certainly a shift from when we started, when many looked at us rather quizzically! Today, we are all more accepting of the adverse effect that we – as humans – have had. There seems to be a far greater public awareness that the individual butterfly effect that we all have – that every choice we make, every item we buy, or consume, tugs on a thread that is connected to some forest, river basin, coral reef or local person in a far-off country.

And yet with all this knowledge, our overall collective response has been feeble, at best. Sadly sometimes, the most evident concerns are the hardest to fix.

The late novelist David Foster Wallace spoke at a College commencement address a few years ago. He opened with a parable:

“Two young fish were swimming along when an older fish swims by, and says ‘Hi boys, how’s the water?’ The two young fish swim on and then one turns to the other and says, ‘what the hell is water?’”

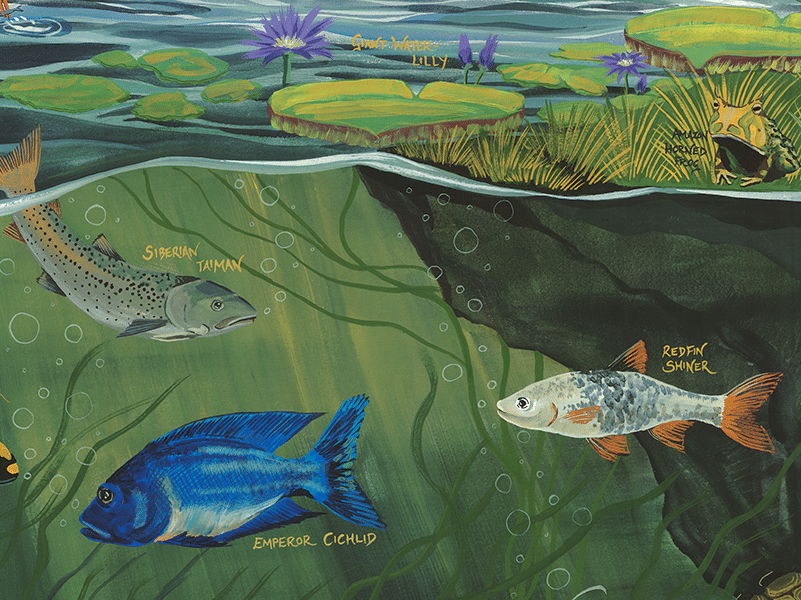

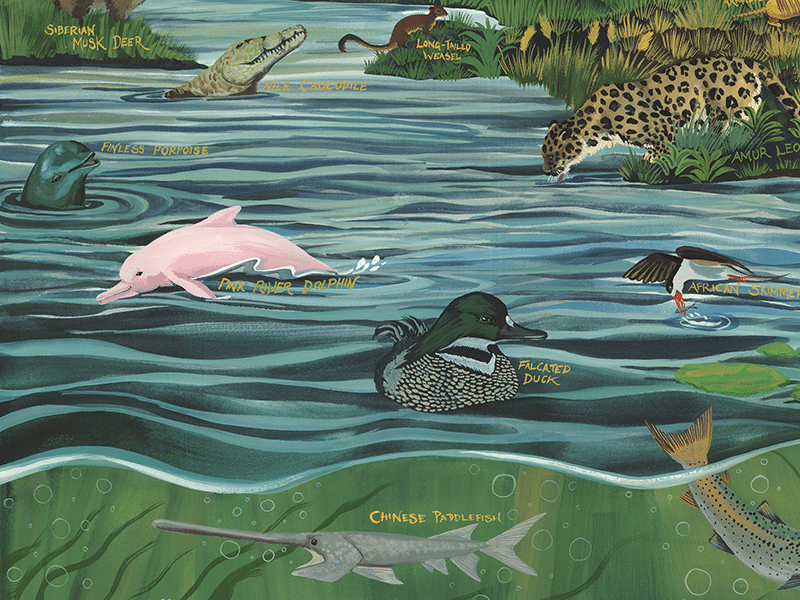

© Alice Shirley

The point is this: the most obvious, and often most important realities are often the hardest to see and talk about. They are the hardest to change.

The parable is actually of Ewe origin – the Ewe are a people from the coast of West Africa – in the Togo, Benin, and Nigerian region. Expanding upon the meaning, for them, this proverb is also about “taking things for granted” and similar to the saying that familiarity brings discontent.

When it comes to the environment, we often take much for granted. And our familiarity – how we are used to being – has contributed to our inaction.

We are cultural creatures – culture shapes us, and we shape culture. This is the history of humankind: this is our story. Our relationship to nature – positive or negative – is embedded in, intertwined with, defined by and defining our culture.

If we accept a fundamental principle of life – that everything is connected – it follows that we should actively protect the fabric of life – it makes good sense. We shouldn’t be accelerating extinction. It also follows that when we deny the rights of cultures that revere life to live as they have done for millennia, we are doing ourselves a great disservice.

© Alice Shirley

Making these connections – bringing conservation and our relationship to nature to life – as impossible as it sometimes feels – is what drives me.

Ten years ago – the conservation sector felt one dimensional to me. It certainly felt like it wasn’t having anywhere near enough impact, it was treating a symptom, and not connected to other issues – like health or refugees.

That was our entry point.

From that moment on, we used every creative approach within our means to shout from the rafters – ‘ecological crisis, coming to a theatre near you’ – this is what you can do about it!

We have worked with artists – Alice Shirley, Louis Masai, Clare Shenstone, Alison Sudol, Mattias and Iris Alexandrov Klum – masters of expression, who help us capture the beauty in nature, who help us feel our way into the emotion of that beauty and also the potential loss.

We have hosted numerous dialogues – the art of conversation – pairing experts with the rest of us, to create forums for discussion so that we can all explore and unpack complex issues that might not otherwise receive our attention – like oil palm, or the amphibian crisis – together.

We have focussed on everyday topics – like food, health, well-being and fashion – again with the most incredible experts – like Satish Kumar, Johan Rockstrom, Arizona Muse, and Livia Firth – so that we might all better understand how our daily choices really do matter.

We have partnered with organisations like the Environmental Funders Network to showcase incredible philanthropists giving back to nature – like Lisbet Rausing, Kris Tompkins, Gunhild Stordalen and Andre Hoffman – in the hope that we might inspire more giving.

We have celebrated! – perhaps ironically – donning beautiful hand-painted masks of critically endangered species at our Biophilia Ball, becoming threatened animals, plants and fungi for a night. And we danced our way to the end of the world at our Last Chance Casino, where every bet had a deeper meaning, a consequence – it’s now or never.

© Alice Shirley

And we have helped launch movements alongside our Advisors – again in areas where there have been voids – like Conservation Optimism – which has created a global community of young, emerging and more seasoned practitioners who are all doing and celebrating what works; or with Flourishing Diversity – creating a platform to bring Indigenous People to the fore, so that their voices – and wisdom about protecting and living in harmony with nature – is not forgotten, but heard, and heeded.

People ask me – what’s next? And I usually say, more of this – much more of this. In a perfectly balanced world, conservation wouldn’t have to exist. But we have a way to go. And we cannot get there without you.

The science tells us that the biggest issue of our time is the ecological crisis, yet philanthropy has hardly responded. One of our goals is to shift this. As you consider your own individual roles in what you can do to protect and restore nature, remember that Synchronicity Earth can help you. This is why we exert influence and shift awareness where we can. This is why we engage with different kinds of culture and meet and connect to a diverse array of people and sectors. It is so that we can be armed with as much knowledge as possible, and relevant leverage to help you, help us make a difference.

Feeling inspired? Education is the first step to action.

Learn more about biodiversity and what conservation is doing to preserve it.